Code with Confidence: OpTiMSoC Always Works!

OpTiMSoC is a highly complex system. If all goes to plan, software, hardware and tooling work together to form a well-integrated SoC (framework). But as so often, the reality is less gloomy: changing a single line of code anywhere could lead to trouble anywhere else. Finding out about breakages only weeks of months after the fact makes debugging a nightmare. [1]

Not any more. After multiple years of despair and a lot of work we can finally say with confidence: “OpTiMSoC always works!” In this blog post we’ll have a look at how we achieved this goal.

The first ingredient to our solution are (automated) tests.

OpTiMSoC comes with many tests on various levels up to the full system level; just type make test in your OpTiMSoC source tree to execute them.

But: the best tests are useless if they’re not run.

And that’s the problem:

Compiling all parts of OpTiMSoC and running the tests takes multiple hours.

Expecting developers to run all of them after every single change is unrealistic.

So we need a better solution, and the answer is (as so often) automation.

In this case, the automation is called Continuous Integration, or CI for short.

CI is is not a new concept, of course. It has been used in software development for almost two decades now. Unfortunately, testing and CI in the hardware world are a bit more complicated than in the software world.

The first challenge are tools: While many of the tools we’re using are available as open source, not all of them are. Particularly the tools to generate FPGA bitstreams (e.g. Xilinx Vivado) are closed source, and some of them require a license to operate. Another challenge is the hardware itself: running tests on an FPGA board requires (unsurprisingly) an FPGA board, and a way to connect it to the test machine. A third challenge is time: synthesizing an FPGA bitstream takes multiple hours. Hence waiting for the full build and test to complete significantly reduces developer productivity.

Despite these challenges, we found a way to have extensive test coverage and fast developer feedback. A two-staged solution gets us there. The first stage are tests in Travis CI. Travis is a commonly used continuous integration service which is free to use for open source projects. It integrates nicely into GitHub and can be configured to run a build and test script on every check-in, and on every pull request.

We configured Travis to build OpTiMSoC and to run all simulation-based tests using Verilator. If a Travis run indicates a successful build and test, we already know that all steps outlined in the user guide tutorial up to (and including) the Verilator-based examples work as expected.

The second stage goes beyond what Travis can provide, as we now need access to commercial tools, associated licenses, and real hardware (e.g. FPGA boards). Internally at TUM we have access to a hosted instance of GitLab, which comes with (among many other great things) an integrated continuous integration system, GitLab CI. GitLab CI lets you attach “runners” to it. A runner is nothing else than a PC with a piece of software installed, connecting it to the central GitLab server. We have made a couple machines in our lab a “GitLab runner”. All of them have access to our tools installed on a central NFS share, and some of them have FPGA boards connected to them.

Making use of this setup and combining it with over 200 lines of configuration file we have created a fully automated continuous integration system. Every night, a new build pipeline wakes up (so we don’t need to) and crunches data for more than four hours on up to four machines in parallel.

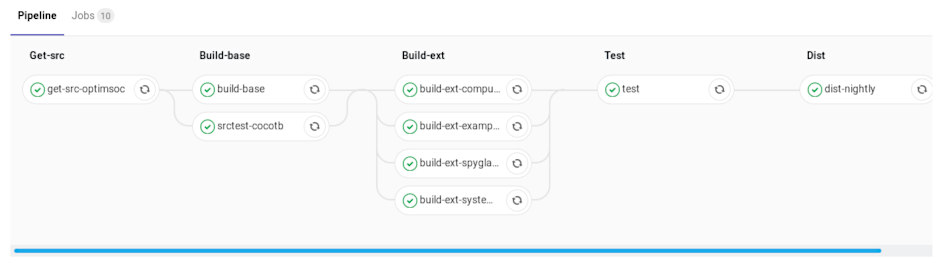

That’s how it looks in GitLab CI:

Looking closer, the build pipeline consists of the following steps.

- Get latest OpTiMSoC source code from the

masterbranch. - Run all cocotb-based hardware tests.

- Run Spyglass Lint on all hardware.

- Build OpTiMSoC itself (that’s mostly software tooling)

- Build seven different Verilator-based simulations models, from a small single-core, single-tile model without debug system up to a 2x2 mesh system with two cores per tile.

- Build four FPGA bitstreams for the Nexys 4 DDR (recently renamed to Nexys A7-100T) and VCU108 boards.

- Run the system tests in simulation and on real hardware. On real hardware, the tests use the Nexys 4 DDR board to run baremetal software, and to build, flash and boot a full Linux!

- If all went well, the resulting build artifacts (source files, simulation models, FPGA bistreams) are uploaded to Bintray, where anybody can download them.

With all this automation in place you can now write a short script to always get the latest nightly build of OpTiMSoC, including FPGA bitstreams.

# figure out the latest version of OpTiMSoC [2]

LV=$(curl -sL https://api.bintray.com/packages/optimsoc/nightly/optimsoc-src/versions/_latest | python -c 'import sys, json; print json.load(sys.stdin)["name"]')

# get the source archive

curl -sLO https://dl.bintray.com/optimsoc/nightly/optimsoc-$LV-src.tar.gz

# get the OpTiMSoC framework

curl -sLO https://dl.bintray.com/optimsoc/nightly/optimsoc-$LV-base.tar.gz

# and finally: get all examples with all bitstreams

curl -sLO https://dl.bintray.com/optimsoc/nightly/optimsoc-$LV-examples.tar.gz

curl -sLO https://dl.bintray.com/optimsoc/nightly/optimsoc-$LV-examples-ext.tar.gz

You can find all CI configuration used for Travis in our main repository (look for the .travis.yml and Dockerfile files).

The results of the Travis runs are also visible online.

The configuration for the GitLab CI is contained in the optimsoc-autobuild repository (look for the .gitlab-ci.yml file).

However, this configuration is heavily tailored towards our internal infrastructure and won’t run anywhere else as-is.

So for now, go and give it a try! Use OpTiMSoC to learn and teach, to explore and discover. Have fun!

[1] At least for light debugging. Heavy debugging, typically performed at night, avoids the problem of nightmares in an interesting way: no sleep, no nightmares.

[2] Getting the latest version first is a bit annoying, having a “latest” symlink would be easier of course. This seems to be a restriction Bintray has for their non-paying customers. Having an additional line in a script is a fair price to pay a free service.