Linux on OpTiMSoC: How many small steps unlock a whole new world

Some projects we take upon ourselves are done quickly: start, do the work, profit. Others take a bit longer. And then there are these projects which seem to linger forever in an “almost done” state. Just one more small thing and we’ll be done. A small fix here. An extension to a module there. A new component elsewhere. And so it goes on, and on, and on. For days, for weeks, for years. Adding Linux support to OpTiMSoC is such a story. But there’s a happy end: Linux support has finally arrived!

This blog post tells the story of how Linux can be now used on OpTiMSoC, and shines a bit of light on the obstacles along the way.

How it all looks in the end

A picture is always a good starting point, so let’s start with a picture.

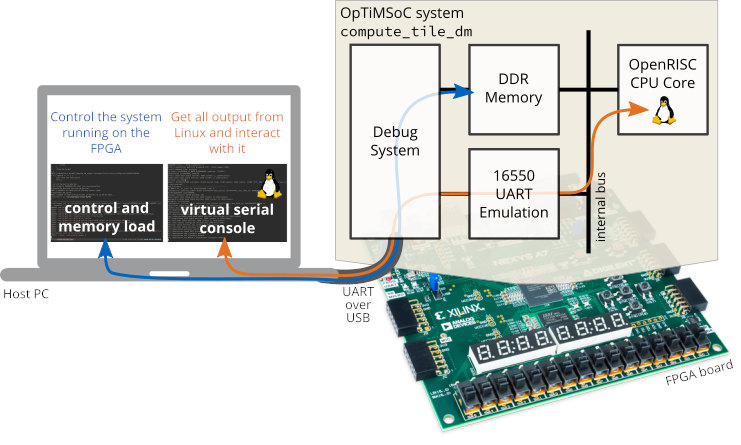

The picture shows a simplified version of the whole system we’ve set up to run Linux on OpTiMSoC. On the left is the “Host PC” where the developer sits. On the bottom at right is the FPGA board, in this case a Nexys 4 DDR board (recently renamed to Nexys A7-100T) containing a Xilinx Artix 7 FPGA (the XC7A100T to be exact). The board is connected to the Host PC through USB, and the FPGA is programmed with a bitstream containing our SoC design.

The design (all described in Verilog) is shown on the top right. At its center is the Wishbone bus which connects a single OpenRISC CPU core, DDR memory, and a 16550 UART module (we’ll get to that in a minute). Supporting this infrastructure is the debug system. It connects to the memory and the UART and enables them to speak with the Host PC.

What we want to achieve (and what not)

Before we go into all the gory details, let’s first discuss the goals of this whole exercise.

- We want to have a Linux-based operating system running on the OpenRISC CPU core on the FPGA.

- We want to see the output produced by Linux (e.g. during boot), and we want to interact with it by typing commands and seeing their output. We call this way of interaction “virtual serial console.”

- We also want to use the Host PC to control the system on the FPGA: we want to load our Linux operating system into the memory on the FPGA, and we want to start and reset it.

To avoid confusion, let’s also discuss the things we don’t want to achieve.

- We don’t have a monitor connected to the FPGA. Our only way of interacting with the system is through the virtual serial console.

- We don’t have persistent storage hooked up to the system, like an SD card or flash memory. Once the FPGA is turned off all software is gone and needs to be loaded onto the system again through the Host PC.

With the goals and non-goals clearly stated let’s have a look at how all this machinery can be brought to life.

Let’s cook up a Linux system on OpTiMSoC!

Before we can get started we first need to prepare our “ingredients”. Don’t worry for now if you don’t know where to get these “ingredients” from, we’ll discuss that later.

- A bitstream for the FPGA containing the SoC design as shown in the picture.

- Software on the Host PC (which also runs Linux) to interact with the FPGA.

- Finally, we need a Linux root image. That’s the software which we will execute on the OpenRISC CPU.

With everything prepared let’s start our recipe, the steps we need to take to boot up Linux on OpTiMSoC are simple.

- Program the FPGA with the bitstream.

- Connect to the system through the debug infrastructure.

- The host software detects the UART emulation module on the FPGA and provides a virtual serial port (e.g.

/dev/pts/1). - On the Host PC, open a terminal application and connect to the virtual serial port.

- Write the Linux root image to the DDR memory using the host software.

That’s it! Once the Linux root image has been written to the DDR memory the CPU starts executing it. In our case, that means Linux boots, and as soon as that’s done, greets you with a login screen: “Welcome to OpTiMSoC”! You can now log into the system as root user, and interact with it as you would do with any other Linux system.

Don’t believe me? Have a look at the video then.

Where do all the components come from?

Everything you’ve seen in the video is using published components of OpTiMSoC. Head to the download page to get the latest release. This gives you pre-built versions of all tools and bitstreams used in this demo. The only thing you need to build yourself it the Linux image.

The Linux root image we’re using is similar to a self-extracting ZIP file: it contains the Linux kernel together with an initial ramdisk (initramfs).

That’s essentially a “hard drive image” loaded into memory, with all tools contained in it: a shell, tools like ps or ls, and additional software we chose to add.

To prepare such a image we are using buildroot, a project dedicated to exactly that purpose.

Buildroot takes a configuration file as input, and produces a vmlinux file as output.

That’s just normal ELF file which we program into the memory on the FPGA board.

All our custom configuration is contained in the optimsoc/optimsoc-buildroot repository. The user guide contains detailed instructions how to make it all work.

Why did it take so long?

The system shown above looks sufficiently simple, doesn’t it? That’s what we thought as well, and again and again. It turns out, to have something as complex as Linux running on a custom system actually requires getting a lot of small and by itself insignificant details right.

- The off-chip connection must be fully reliable. Making sure that no packets drop, even in rare backpressure scenarios, took a while. Max did great work in creating stress tests for our UART and USB3 interfaces (all of them part of GLIP) and debugging their fallout. Some days and nights went into the firmware for the Cypress FX3 chip, which doesn’t always behave as the datasheet would make one think …

- The second ingredient is of course Linux itself. Stafford Horne did a great job to pick up work on the upstream Linux port and to steadily improve it. Today, we can run an unpatched upstream Linux kernel on our system!

- One of the last steps was to add the DEM UART module to Open SoC Debug. This module emulates a 16550 UART device so that Linux can use its standard drivers to communicate. But instead of sending all data to a physical UART port, the DEM UART module wraps it into Debug Packets, which are sent through the debug interconnect to the host PC, reusing the same infrastructure we use for loading the Linux root image into the memory. This last step was completed by Thomas Leyk a couple of weeks ago.

- Finally, we needed a way to reproducibly build a Linux root image. Thankfully, that’s rather easy thanks to buildroot.

Not mentioned here is all the time spent on debugging small issues, fixing the build automation, and adding tests to ensure we don’t break our newly gained Linux functionality any more. Today we have a full Linux build happening every night, performing the exact same steps as you’ve seen in the video, and checking its outputs.

Get started

Do you want to build your own Linux image for OpTiMSoC? Do you want to try out what you’ve seen in the video? Then head over to the tutorial in the user guide!

With Linux running on OpTiMSoC we’ve unlocked a whole new world of possibilities – software can run with minimal porting effort, existing drivers can be reused, and much more. The future is bright, and we’re excited to explore more ways of using OpTiMSoC!